The Master’s Field

by Fran Olson

From “In Other Words,” Summer 1978

A Drama of an Incredible Crop

Setting:

The Field--Chipaya, Bolivia

The Plants--Chipaya Believers

The Seed-God’s Word

The new strain of Seed--the Chipaya New Testament

Cast:

Master of the Harvest--The Lord

The Sowers--Ron and Fran Olson

Friends of the Master--Team members at home

The Squatter--Satan

Scene I, Twenty Years Ago.

The Master of the Harvest looks across His fields. One of them is completely dry, barren, rocky. Not a green leaf grows. The sinister Squatter living there likes it that way. But not the Master.

Who should plant His Seed there? He looks around and chooses two Sowers, then has them study about the Seed, methods of planting it, watering it, soil preparation, and nurturing the sprouts. Where? In the Quiet Place and also in college, Bible school, seminary, and finally at the Summer Insititute of Linguistics.

Scene II, Fifteen Years Ago.

The Sowers reach the field. It looks hopeless, but they find that a Seed had been dropped and one small plant is growing. So they know the ground, barren as it seems, can produce fruit. Hopefully, they start breaking up the hard, dry clods. How? By fixing bikes, giving medicines, joining in village projects, sewing rag dolls and being a bridge to the outside world. Seeds are dropped here and there.

The Squatter snears as he watches, sure that their efforts are all in vain. But many Friends of the Master water the field with their prayers. Still the ground seems very hard. Very poor. Very dry. The Sowers kneel before the Master of the Harvest, praying for at least a small crop.

Scene III, Ten Years Ago.

Happy day! Six little shoots break through the hard crust. Water! More water! Now the cruel Squatter, alarmed, sends freezing ridicule and scorching persecution, but the Master sends warm sunshine and His Friends faithfully water the tender shoots. They start to grow. The Sowers clap their hands and thank the Master of the Harvest for the promise of a crop.

Scene IV, Five Years Ago.

Sturdy plants dot the field, and some are even beginning to reproduce. The Seed is continually being sown, and a new strain, especially adapted to this field, is being produced. Now the Squatter is furious. This new Seed takes root more quickly and produces plants more resistant to his scorching heat and freezing winds.

The Sowers marvel at the miracle which is transforming the field. What is the secret? The warm sunshine of love from the Master? The constant watering by His Friends? The new strain of Seed? Surely they all play a part. With hearts full of praise the Sowers bow before the Lord and praise Him for the anticipated yield.

Scene V, Now.

About half the field is producing good fruit. Most plants are strong and tall, producing rich fruit and sheltering the new little shoots. The Squatter fights for every inch of soil, but he sees in dismay that it’s a losing battle. Deperately, he sows tares and thistles as fast as he can, but the new strain of seed is also being sown. Now the life of the plants is transforming the soil, and they are reproducing themselves. In joy and wonder the Sowers thank the Master of the Harvest for choosing them to be part of this miracle. And all the Friends of the Master rejoice with them and continue watering--for to stop now would permit the Squatter to reclaim precious sections of the field.

Back to Top

Chipaya dancers circle before a house topped by a straw cross symbolizing the house’s protecting angel. |

Free to Worship?

by Fran Olson

From “In Other Words,” February 1980

The drumbeat quickened to a loud crescendo, then stopped short. Carlos leaned against the adobe wall, dropping his sticks in the cold sand. His fingers were numb. So were his sandaled feet. Even through his thick wool poncho he felt the icy wind that swept across the barren plains. In the thin grey dawn he could barely distinguish his Chipaya companions--men in homespun tunics and trousers; women in dark dresses with babies on their backs.

Carlos was proud to be a Chipaya, for they had never been conquered, not even by the Incas. They had always been free--free to live and worship as they pleased. Carlos reached into his pouch for another wad of coca leaves, hoping they would lessen the cold and dull the ache in his head. They had been dancing and drinking all night and must continue all day till sundown. How else could they pacify the river spirit and be assured of good crops? Two years ago when the river was low the sun parched their “quinoa” grain, and last year it washed their crops away. They couldn’t take another lean year!

Carlos fished inside his tunic for a tiny aluminum cup as the fiesta leader made the rounds, pouring alcohol from a grimy little teapot. A good leader filled their cups often.

After they had all drunk and rested a bit, Carlos picked up his sticks and started the rhythm again. One by one, wooden flutes and panpipes joined in. Mechanically the men and women rose and half danced, half marched around the open plaza which separated the two sides of town, then wound their way between clusters of little round huts.

Finally the sun crept over the horizon, chasing away the shadows. They stopped for another drink, grateful that the long cold night was over. Carlos looked around the group of dancers. Every Chipaya used to join in the rituals till some foreigners came to live among them, bringing medicines, writing down their words, and teaching about a God Who was greater than the spirits. The medicines were all right, but now some of the people had left the old ways to serve this “new” God.

Take Ceferino, for instance. He used to drink to the spirits at every fiesta. He refused to take part at all now, saying he was free to worship whom he chose, and now he worshipped the “true” God. Of course he was free; they all were. But how could he be a true Chipaya and not worship the spirits? Besides, it was unfair not to help appease them--and dangerous, too.

Just then Ceferino hurried by on his way to the village well. Carlos stopped him and threw an arm around his shoulder, breathing in his face. “Ceferino, brother, drink with us to the river spirit,” he urged, pressing the little cup to his lips.

But Ceferino shook his head. “No, brother. I’ve entered God’s Way and worship only Him. You should follow Him, too, Carlos. He’s a good God. These ways always end bad. You know they do...”

Carlos turned away, muttering to himself. It wasn’t his fault people picked on him when he was drunk.

The other men crowded around Ceferino, offering their drinks in a friendly way at first, growing angry when he refused them, but he finally managed to get away.

Disgruntled, the crowd continued drinking and dancing. Before long Carlos’s poncho felt hot and heavy. He was relieved at last to stop at the fiesta leader’s house, but he was glad it wasn’t his animals that would be sacrificed. He joined the circle and helped sprinkle coca leaves and alcohol on the llama, pig and sheep. Then, bleary-eyed and groggy, he sagged against the house and dozed till the pig’s squeals roused him. Now they were pouring the blood on the ground for the river spirit. Would he be content for another year? Only time would tell.

The rituals completed, Carlos reluctantly started drumming again. As the hours dragged by, his thoughts kept turning to Ceferino. Who ever heard of worshiping a good God? If He couldn’t eat your child’s spirit or ruin your crops, why worry about Him? His wife wished he’d quit fighting and going off with other women at all the fiestas, but if he didn’t drink, the spirits would be offended and his friends would despise him--like they despised Ceferino! No, that was too much. God’s Way might be good, but it wasn’t for him. Maybe some day. After all, he was free to worship whom he chose.

As the blazing sun beat down, the group dwindled. His head was pounding. The music was muddled, the dancers sluggish. Why were the spirits so hard to please?

It seemed like an eternity before the fiery sun sank toward the distant mountains, signaling time for the sacrificial meal. Now crowds gathered from all over the village for the free food--piles of steamed quinoa and five-gallon cans of quinoa soup. Carlos drank two big bowlfuls of soup, devoured a hatful of the fluffy quinoa and boiled corn, then chewed on the tough meat. For awhile the food and cool shade helped him forget the throbbing in his head.

As soon as the sun disappeared, the chill crept back across the barren plains. Again his poncho felt good. The food was gone. The fiesta was over. Some folks were staggering home, supporting each other. Little children tugged at their mothers’ skirts, begging them to come. Carlos’ wife pulled at his poncho, pleading, “Please come home before you get in trouble!” But how could he leave now? The fiesta leader was still supplying drinks! He pushed her away and crowded into the small round hut with other men and women, slouching on the sheepskins that carpeted the dirt floor. By flickering candlelight they continued drinking. There was hoarse laughter. Arguing. More drinking.

Finally Carlos had had enough. He edged closer to the woman next to him and said, “Let’s go.” She eyed him scornfully and turned away.

“I say, let’s go!” he insisted, grabbing her arm.

She pulled away and slapped his face, muttering, “Leave me alone!”

No one was going to treat him like that! Enraged, he felt around on the dark floor till his hand found a bottle. He clutched it and swung, breaking it on her head. She screamed, but he swung again. With a moan she slumped over, blood streaming down her face. Terror gripped Carlos. What if she died? What would her husband do to him? Why did fiestas always end this way? His companions crowded around, yanking at him and shouting. Desperately he jerked away and escaped into the blackness. The fresh air and cold wind in his face helped him think. The foreigner--Tall Brother--maybe he could help! Blindly he stumbled across the dark plaza. Yes, Ceferino was right. These ways always ended badly. He had had enough.

Reaching the translator’s house, he banged on the door till it opened, then stumbling into the room, he fell on his knees before the translator, sobbing, “Tall Brother, please help!”

Tall Brother pulled him to his feet, saying, “Don’t kneel to me; I’m just a man. What’s wrong?”

“It’s Viviana--her head--it’s bleeding! Please come!”

Tall Brother was already reaching for bandages and medicines and lifting the kerosene lantern off its hook.

As the two men hurried back across the plaza Carlos was still sobbing. “The old ways--they’re no good. I’ve had enough of them. I’m going to enter God’s Way, like Ceferino. Really I am, brother--tomorrow--when I’m sober--tomorrow--I really am...”

But tomorrow came and went and Carlos just couldn’t make the break. The deep gash in Viviana’s forehead began to heal. Her husband demanded several precious sheep in payment, but the community soon forgot the incident. The weeks passed. More fiestas came. Carlos didn’t want to take part, but how could he offend the spirits? And how could he refuse to drink with his friends? Again he drank. Again he fought. Then at last he realized he wasn’t free. He was a slave!

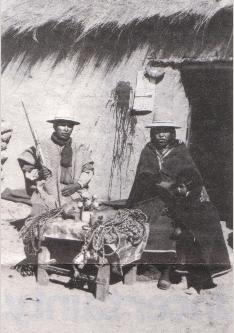

Formerly the entire Chipaya community participated in the fiestas, but now only a small group worships the spirits, since many Chipayas have become believers. |

A Chipaya mayor holds in his right hand “our father king” (the shorter pipe) and “the spirit’s wife” (the long slender pipe). The blood on the wall of his house is from a sheep, llama, or pig sacrificed to the house spirits. Plastic flowers, armadillos, and woven wool ropes adorn the table. |

Back to Top

Verses for New Believers

by Ron Olson

From “In Other Words,” October/November 1985

“You cannot drink the cup of the Lord and the cup of demons too; you cannot have a part in both the Lord’s table and the table of demons” (I Cor. 10:21). Have you ever heard a sermon preached on that text? I have, but not from the English Bible.

When we first went to live among the Chipaya people on the cold, windswept 12,000 foot high tableland of Bolivia, we found the people in bondage to evil spirits. They performed hundreds of blood sacrifices to appease them, and each fiesta had ritual meals to honor them.

“What about the good spirits?” we asked.

“Good spirits?” they replied. “We never thought much about good spirits. It’s the evil spirits we’re worried about--the ones that eat our babies’ souls, destroy our crops, and cause us to get sick and die.”

After a blood sacrifice the Chipayas would begin the dancing, and with each cup of watered-down alcohol they would drink to the demons. At the end of the day everybody would gather in and around the house of the fiesta leader to partake of a meal honoring the spirit. Inside the house they spread a small blanket on the gound, and heaped fluffy, cooked quinoa grain on it in a large ring. This formed the table of the spirit. First a bowl of soup would be served to each person, then a bowl full of quinoa and perhaps some boiled corn.

Some Chipaya Christians said it was alright to eat and drink to the spirits--if they didn’t get completely drunk. But one Sunday Maximo, one of the believers, made the issue very clear. He had come across the Scripture which says you can’t partake of the Lord’s cup and the cup of the demons; you can’t worship the Lord and the devil, too. That settled the question.

We all need God’s Word in our own language, so He can speak directly to our needs. If we were choosing verses to give new believers, we probably would not include I Cor. 10:21. But it is an important verse to the Chipayas, one that helped them resist the temptation to be drawn into the fiestas associated with demon worship. Now Christian fiestas are taking the place of the old ones, and the Christians are trusting in the all-sufficiency of Christ’s blood.

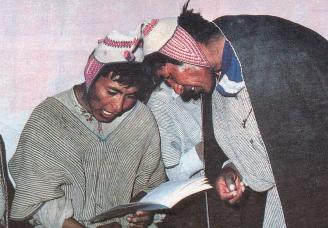

After a long day’s work, Chipaya pastor Maximo teaches an adult literacy class. |

Back to Top

|